The Qing Dynasty: China’s Last Imperial Age

Hugo Van der Merwe

Hugo Van der MerweLearn Chinese in China or on Zoom and gain fluency in Chinese!

Join CLI and learn Chinese with your personal team of Mandarin teachers online or in person at the CLI Center in Guilin, China.

Founded by Manchu warriors, the Qing dynasty was once a continental force to be reckoned with. Stretching across the entire eastern half of Eurasia, it had tributary states from Siam to Sikkim. By the time that the last Qing emperor sat on the throne, however, it had already been the victim of multiple invasions and rebellions and was teetering on the brink of economic collapse. Read on to discover how this dramatic story unfolded.

Table of Contents

The founding

To understand the story of the Qing, it's necessary to gain a basic understanding of the dynasty that preceded them: the Ming.

The Ming

The Ming dynasty (明朝 Míngcháo) started the way almost all Chinese dynasties start: as a rebellion. After overthrowing the Mongol-dominated Yuan Dynasty (元朝 Yuáncháo), the ethnically Han Ming rulers asserted control in 1368 CE.

Under the great Yongle emperor, the Ming expanded the frontiers of China and ushered in a period of prosperity. In a decisive break with the past, the Yongle emperor also moved the capital to the north, giving it the name “northern (北 běi) capital (京 jīng),” or Beijing (北京 Běijīng).

After many years of neglect, Ming rulers resurrected the ruins of that most Chinese of engineering marvels: the Great Wall of China. Peasants were dispatched in droves to fortify this crumbling piece of China’s defensive patrimony.

Under the Yongle Emperor’s leadership, Ming China’s frontiers expanded and the dynasty prospered.

In 1420, at the height of their power, the Ming rulers also launched the largest exploratory fleet the world had ever seen. Under the guidance of admiral Zheng He, the Ming dynasty became renowned throughout the world. His journeys took him throughout the Indian ocean, Indonesia, the Arab world, as well as to the eastern coast of Africa. The giraffe that the expedition brought back to Beijing was a sensation.

Likewise, Ming rule saw the flourishing of the arts. To this day, elegant, intricately patterned Ming vases are best sellers at art auctions around the world.

However, the Ming were not immune to the cyclical tale of dynastic rise, decadence, and fall. By the 16th century, peasants across the empire were rising against the local government, incoherent economic policies had led to fiscal collapse, and internal elite divisions and court intrigue had taken on feverish dimensions.

Meanwhile, non-Han subject peoples had rejected even the pretense of submission and were making regular military incursions into Ming territory. Successive economic crises and general dissatisfaction with a political elite had stoked the flames of revolution. One of these rebellious non-Han groups, the Manchu, would go on to overthrow the Ming and found the Qing dynasty.

As the Ming dynasty declined and fell, the lives of members of the Han elite, like the artist Shitao (pictured here) were thrown into disarray.

The Manchu

The purposeful destruction of their earliest records, the repeated rewriting of Manchu history, and the sinicization that eventually overtook them makes for a confused Manchu origin story. Even the name “Manchu” was a late invention, chosen by the founding Qing emperor to obscure the fact that his ancestors (then known as the Jurchen people) had once been subject to the Ming emperor.

What we do know about the original Manchu people is that they were descendents of the rulers of the 10th century Jin Dynasty (晋朝 Jìncháo). The Manchu had abandoned their nomadic ways and been settled agriculturalists for centuries by the time they founded the Qing dynasty. However, they still emphasized mastery of traditional skills like outdoorsmanship, hunting, fishing, and equestrian ability. Another deeply ingrained cultural trait was a fascination with falconry—even today, one finds this tradition alive and well.

Originally a nomadic people, the Manchus of the Qing dynasty valued mastery of traditional skills like horseback riding.

Renowned for their skill as mounted archers (an ability that was to come in handy when they swept out of northeastern China to shatter the Ming Dynasty), they hunted small game on horseback for both food, sport, and prestige.

Culturally, the Manchu maintained a comparatively high level of gender equality, with women having a larger say in the household and being permitted more room in the public sphere than their Han peers.

Originally followers of a shamanistic religion that revolved around the appeasement of the ancestors, after their ascent to power they were increasingly drawn to Confucian practices, eventually embracing and patronizing Tibetan Buddhism. Many of the magnificent Buddhist temples that dot Beijing are the result of Qing piety.

Although the Manchus were once followers of their own shamanistic religion, they eventually came to embrace Buddhism.

A victorious rebellion

Before overthrowing the Ming, the Manchus were based in northern China. The first three Qing emperors lived in Mukden Palace, in present-day Shenyang. From there, they waged a relentless rebellion against the Ming.

After several years of war, Manchu rebels sacked and occupied the Ming capital of Beijing in 1644. On a hill overlooking the burning city, the last Ming emperor committed suicide.

In desperation, the Ming general who manned one of the central gates of the Great Wall that led into China proper turned to the Manchus, inviting them to join him in reclaiming the capital in the name of the dead emperor. Upon successfully retaking the capital, the Manchu promptly decided that, in fact, they had no desire to return the capital to the Ming.

The Manchu declared that they were now in possession of the Mandate of Heaven and moved their capital to Beijing. Although the conquest of China was only completed in 1683 because of resistance from Ming loyalists and other rebels in the south, the Qing’s time had arrived.

After many years of war, the Manchu rebels finally overcame the Ming resistance in 1693.

The prosperous age

The period from 1683 and 1839 is known as the High Qing era. In Chinese, it’s also sometimes called the ‘Prosperous Age of Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong’ (康雍乾盛世 Kāng Yōng Qián Shèngshì) in reference to the emperors who ruled over this period of good fortune.

Shrewd Qing governance (borrowing the best practices of the Ming Confucian bureaucracy while still allowing for adaptation and innovation) led to a prolonged period of economic and political stability.

Instead of attempting to uproot and replace the institutions of the previous dynasty, the Qing presented the Manchu imperial system as an outgrowth of the Han Confucian system. Loyalty to the Qing was equated with loyalty to the ancestors.

This period of stability led to a burgeoning population which in turn gave rise to an increased tax base. This virtuous cycle continued for a number of decades.

The Manchu displayed a talent for co-opting Han traditions to suit their own needs.

Expansion by land and by sea

From 1750 to 1790, the Qing empire reached its greatest territorial extent. The Qianlong Emperor led a total of ten relentless campaigns into inner Asia which extended Qing dominion over wide stretches of land that had previously been outside of China proper.

Tibet, Hainan and Taiwan all submitted to Qing rule. Similarly, the conquest of what is today Mongolia was completed in a series of expeditions in the latter half of the 17th century. Qing armies also conquered what is now Xinjiang in a series of campaigns between 1755-1758.

The Qing at its height was the fourth largest empire in history, ruling over 5 million square miles (13 million square kilometres) of territory. From the Himalayas in the west to the Gobi in the north, 450 million people lived and died under the rule of the Qing emperor, known as the son of heaven.

In its heyday, the Qing was the fourth largest empire in the history of the world.

The tributaries

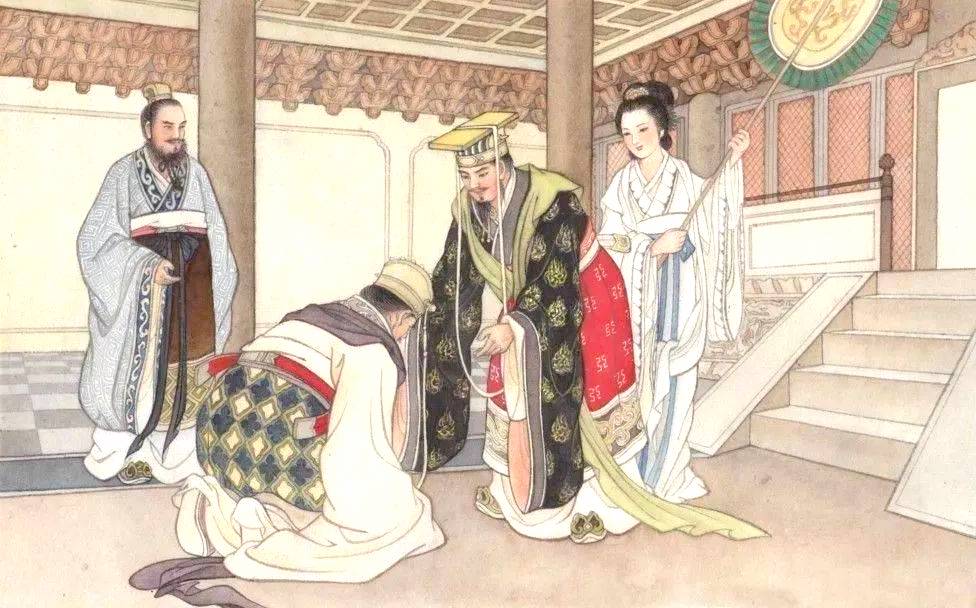

Already in 1636, before the formal establishment of the Qing Dynasty, the emperor Hong Taiji had invaded Korea. Under the Qing, Korea was forced into what was known as the 册封体制 (cèfēng tǐzhì) or the tributary system. Under this system, envoys were required to come to the royal court, present gifts, and kowtow to the emperor, acknowledging his superiority. For many years, access to Chinese trade was made contingent on accepting the terms of the tributary system which required that tributaries recognize the emperor as the one and only Son of Heaven.

In practice, this system contained a multitude of gradations of actual control. Some countries, like Vietnam and Korea, were tightly controlled for decades and were essentially vassal states of the empire.

Others, such as the Katoor dynasty in Afghanistan, were much less tightly bound to the crown, although they still sent tributary gifts and recognized the sovereignty of the Qing emperor.

Under the tributary system, the rulers of many of the states bordering China were expected to present gifts to the Qing emperor.

Wise emperors

At their best, Qing emperors displayed a knack for borrowing ideas, cuisines and titles from their vast array of subject peoples. For example, in interactions with their Han subjects, Qing emperors utilized the Chinese 皇帝 (huángdì), while among Mongol subjects, they instead borrowed the more locally resonant title “Bogd Khaan.” Likewise, among the Tibetans, they were known as Gong Ma.

The use of such tactics helps explain how they were able to hold together their sprawling, multi-ethnic empire using a delicate balance of persuasion, attraction, and coercion.

Specific emperors’ personalities were also key to maintaining this balancing act. Luckily, the Qing were blessed (especially in the early years) with a number of wise emperors.

Hong Taij was the founding emperor of the Qing dynasty and certainly among the greatest in his line. His central insight was understanding the need to attract the ethnically Han Chinese to the Qing cause. His father, Nurhaci, had legalized discrimination against his Han subjects and placed them in a position of subservience to the Manchu. These actions had made them unwilling to join the ranks of the bureaucracy or the army and even prompted a number of peasant rebellions.

Hong Taji reversed these policies, incorporating Han men into the military. He also adopted many elements of the Confucian bureaucracy which helped keep the nascent empire’s wheels spinning.

Xuanye, known as the Kangxi Emperor, was another master of uniting a wide array of interests in the Qing cause. For example, he saw Jesuit missionaries as valuable sources of military, mathematical, cartographic, and astronomical knowledge and employed them in his court. Despite resistance from Confucian traditionalists, he knew that knowing more about how the wider world operated would make China stronger.

The Kangxi Emperor was a wise ruler who enlisted the help of Jesuit missionaries to expand Qing understanding of the outside world.

The collapse

The reasons behind the Qing dynasty’s ultimate disintegration are manifold. However, they can be summarized as: economic mismanagement, foreign predation, elite disconnect, and consequent rebellion.

The Taiping Rebellion

The outbreak of the Taiping Rebellion in the mid-19th century was the first sign that the foundations of the Qing empire were beginning to crack. This was also the first time that anti-Manchu sentiment was weaponized at scale.

The rebellion was led by the young and charismatic Hong Xiuquan. He claimed to be the brother of Jesus Christ and to have received visions from God directing him to build a utopian society devoid of the daily torments of peasant life. The society he believed he had been tasked with establishing was known as the ‘Kingdom of Heavenly Peace.’ Seduced by his promises of a better life, millions of peasants flocked to his yellow, dragon-emblazoned banner.

In crushing the Kingdom of Heavenly Peace, the Qing were pitiless.

The chaos of the era makes exact records difficult to come by, but it is likely (when considered in relation to world population at the time) that the Taiping Rebellion was the bloodiest war in world history. From 1850 to 1864, between 20 and 30 million people lost their lives. A melange of natural disasters and brutality on the part of Qing generals turned large swathes of China into an uninhabitable wasteland.

By the end of the 14-year war, Qing forces had regained control of the empire—but at a terrible cost: millions dead, thousands of hectares of farmland destroyed, and China’s international standing permanently tainted by having been forced to call on the military support of France and the United Kingdom.

The Taiping Rebellion may have been the bloodiest war in world history.

The First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) was a highwater mark in the repeated humiliations of China in the face of foreign armies. For millennia, China had overshadowed Japan and jealously guarded its position of centrality in Asia using the tributary system.

By the end of the nineteenth century, however, Japan had modernized its military and economy and was eager to flex its newfound muscle. After years of diplomatic slights, Japan was now prepared to jostle openly with China for control of territory, namely the Korean peninsula and Taiwan.

In a mere eight months, Japan had achieved all of its military objectives. Despite their new fangled training and attempted modernization (part of what is known as the ‘Tongzhi Restoration’), China’s armies had nonetheless performed poorly on the battlefield. The blow to Chinese prestige was swift and severe.

The First Sino-Japanese war was further proof to the other hungry colonial powers (such as France, the UK, and Germany) that when push came to shove, China could no longer offer real resistance to their intrusions, commercial or otherwise.

The loss of the First Sino-Japanese War was a major blow to Qing prestige.

The Boxer Rebellion

What became known as the Boxer Rebellion hammered the final nail into the already decaying coffin of the Qing empire.

Named “Boxers” by the Christian missionaries who observed them training in martial arts, the Righteous and Harmonious Fists (义和拳 Yìhéquán), were a secret society that originated in the Shandong region. Years of severe drought and economic malaise had created a huge surplus population of unemployed youths. This was the main recruitment base for the Boxers.

Their central tenets were a commitment to purging China of foreigners and Christianity. The Rebellion kicked off in earnest in 1900. A force of between 50 and 100 thousand boxers marched on Beijing, intent on besieging the foreign quarter and expelling or executing the foreigners.

The Qing Empress Dowager Cixi, caught between encroaching western forces on the one side and tens of thousands of enraged Boxer militia members on the other, sided with the Boxers and formally declared war on the foreigners.

The foreign powers used the defense of their besieged envoys and merchants as a pretext to invade China. A 20,000 strong military coalition called the Eight-Nation Alliance consisting of American, Austro-Hungarian, British, French, German, Italian, Japanese, and Russian forces crushed the Boxers and entered the capital.

The Empress Dowager fled the capital for Xi’an, but eventually she was forced to sign the Boxer Protocol, a document that authorized the permanent placement of foreign troops in Beijing, the execution of government officials who had given aid to the Boxers, and the payment of crippling reparations.

Following the signing of the Boxer Protocol, the Qing dynasty would survive only another 10 years.

Qing Empress Dowager Cixi made the fateful decision to support the Boxers during the Boxer Rebellion.

The fall

By 1911, the empire had reached its breaking point.

Corruption was rampant and overt. The ossification of Qing elites had created a parasitic class who lacked the ability to adapt to a fast changing world. Decades of economic weakness had undercut the tax base and the burgeoning population that had once been a source of strength now only served to swell the ranks of the rebel groups that proliferated throughout the empire.

The arrival of the technologically superior Western and Japanese powers (who collectively enforced what in China are termed the “Unequal Treaties”) and the unbearable yoke of reparations imposed after the Boxer Rebellion, had created an untenable situation.

Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam had already been wrenched out of the tributary orbit. By the time that Puyi, the last Qing emperor, had come to power, the empire was ripe for collapse.

For years there had been internal calls for reformation and revolution. Qing decadence had created an atmosphere in which Chinese intellectuals were desperate to find a way for China to reclaim its central place in world affairs. Prosperity and an end to the repeated humiliations that China had suffered at the hands of foreign powers motivated them to act.

Foremost among these figures was Sun Yat-sen, the father of modern China. Statesman, physician, political philosopher, Sun Yat-sen was a tireless campaigner for an independent, powerful, and wealthy China, and he believed that a republican form of government would best serve these goals. By rallying to his cause an ideologically diverse band of followers he would, after a lifetime of toil, eventually succeed in founding the Republic of China.

After years of violent contestation, a wave of rebellions swept the empire. With no other choice left, the child emperor Puyi was forced to abdicate, bringing China’s imperial system to an abrupt end. With the departure of Puyi, the Qing empire died and the Republic of China was born.

The Republic of China came into being after the Qing collapsed in the wake of armed rebellion.

Remembering the Qing today

The legacy of China’s last imperial dynasty remains a point of contention to this day.

One major long-term effect of Qing domination was a nascent sense of nationalism among the Han Chinese. During the waning years of the Qing empire, anti-Manchu sentiment served as a powerful motivation for those who wished to resist or reform the regime. Emphasizing the Manchu (and subsequently foreign) nature of the Qing imperial family and highlighting the Han origins of the majority of the Chinese population was a powerful way to mobilize people against the Qing rulers.

However, some scholars have taken another approach to Qing history in recent years. Instead of viewing the Qing as foreign and alien to China, there has been a push to underline the achievements of this period of Chinese history and take pride in this time when (particularly during the High Qing era) China was a dominant and unvanquished force in Asia and the world.

Ultimately, the Qing dynasty’s wealth of cultural achievements, its dramatic ups and downs, and the sheer length of time that it ruled its vast empire means that it has the capacity to be interpreted and reinterpreted in myriad ways.

For better or worse, the legacy of the Qing dynasty continues to influence China to this day.

Qing dynasty vocabulary

| Hànzì | Pīnyīn | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 明朝 | Míngcháo | the Ming dynasty |

| 元朝 | Yuáncháo | the Yuan dynasty |

| 北 | běi | north, northern |

| 京 | jīng | capital |

| 晋朝 | Jìncháo | the Jin dynasty |

| 清朝 | Qīngcháo | the Qing Dynasty |

| 康雍乾盛世 | Kāng Yōng Qián Shèngshì | High Qing era; Prosperous Age of Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong |

| 册封体制 | (cèfēng tǐzhì) | the tributary system |

| 皇帝 | huángdì | emperor |

| 义和拳 | Yìhéquán | The Righteous and Harmonious Fists; the Boxers |

Hugo Van der Merwe is the Sales and Marketing Specialist at the Chinese Language Institute (CLI), where he leads recruitment for CLI's Study Abroad program. He holds a BA in International Relations and Philosophy from New College of Florida and served for two years as a Peace Corps lecturer in China's Guizhou province, where he taught over 700 students across 800 classroom hours. Hugo holds an HSK 5 Chinese proficiency certification, a Peace Corps TEFL certificate, and has lived and worked across China, the United States, Namibia, and Spain.