The Tang Dynasty: China’s Golden Age

Learn Chinese in China or on Zoom and gain fluency in Chinese!

Join CLI and learn Chinese with your personal team of Mandarin teachers online or in person at the CLI Center in Guilin, China.

China’s long history can be confusing. Instead of trying to memorize every single dynasty, it helps to focus on the most important ones. If there’s one period every student of Chinese should know, it’s the Tang dynasty. Read on for an introduction to this exciting age of economic prosperity and cultural diversity.

Table of Contents

The history of the Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (618-907 CE) was a high point for Chinese civilization during which China experienced immense cultural and economic growth.

Tang China is legendary, not just in China proper, but all over Asia. This was truly China’s golden age, when Chinese cultural influence stretched well beyond its borders. A prosperous, cosmopolitan era which saw an unprecedented level of tolerance and acceptance of other cultures and ideas, this is a period that Chinese people still speak of with pride.

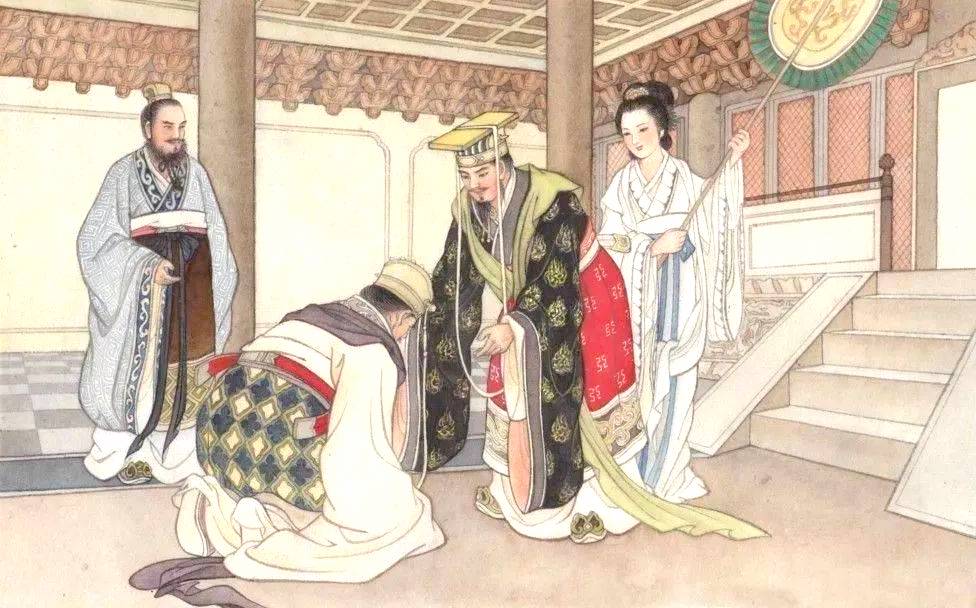

Founding

The Tang dynasty (唐朝 or Tángcháo in pinyin) was founded in 618 CE by Emperor Gaozu, who worked with his second son Li Shimin and daughter Princess Pingyang to overthrow the short-lived Sui dynasty (581-618 CE).

Li Shimin soon seized the throne, forcing his father to retire. As emperor, he waged various military campaigns throughout Central Asia, expanding and consolidating Chinese control over vast swaths of territory. After his death, he was succeeded by his son, Emperor Gaozong.

Emperor Gaozu was the founder of the Tang dynasty.

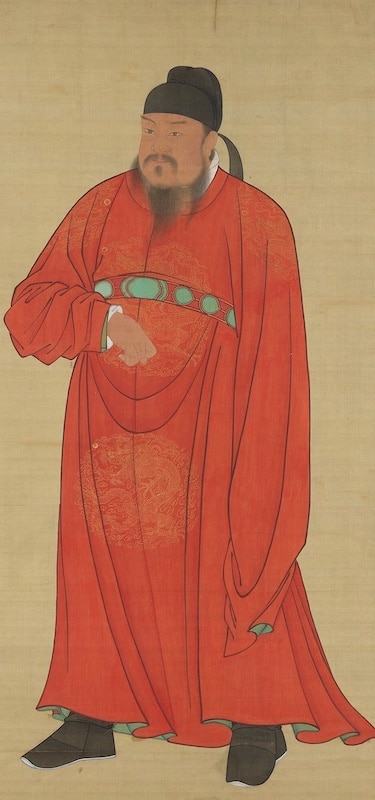

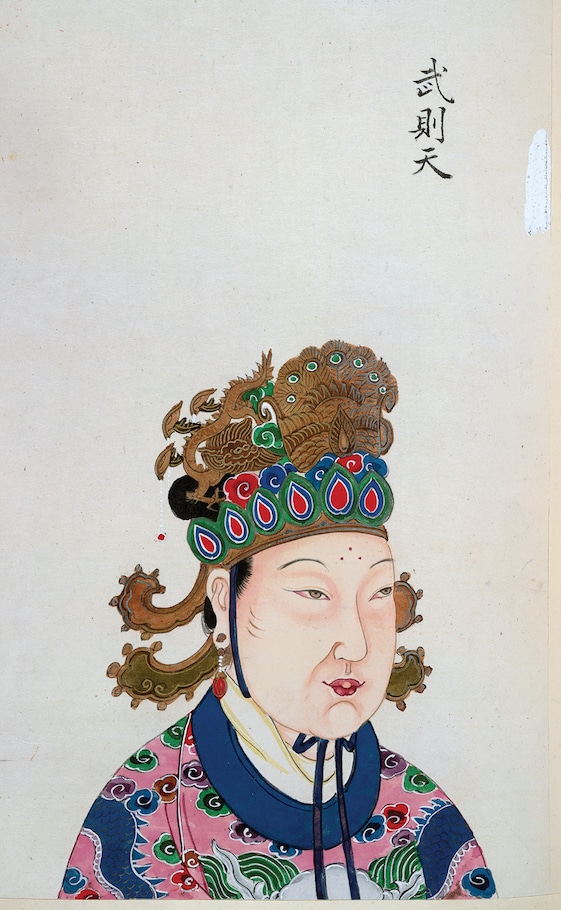

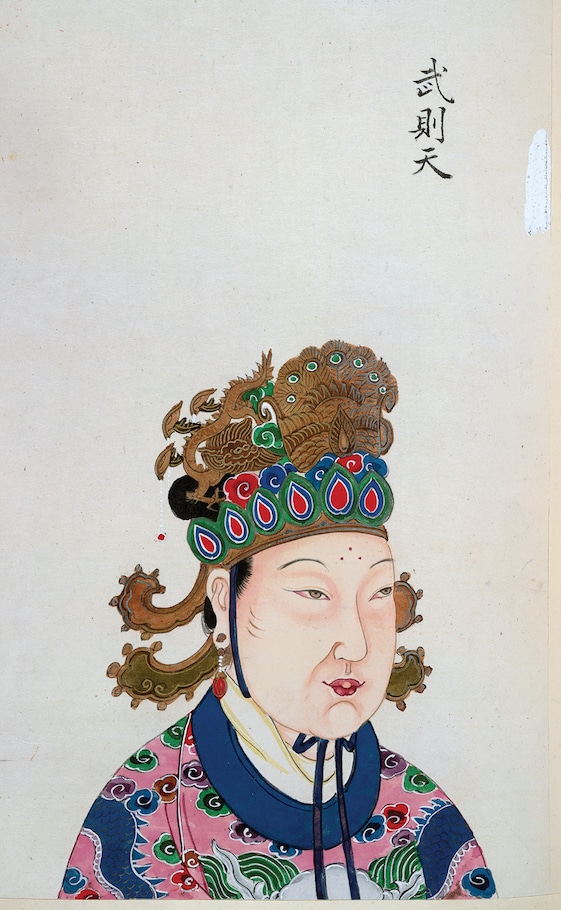

Wu Zetian and the Zhou dynasty interlude

Emperor Gaozong was a sickly and relatively ineffective ruler. His reign was overshadowed by his powerful wife, the ambitious, talented and well-educated Wu Zetian, who would go on to become China’s only female emperor (黄帝 or huángdì).

Wu Zetian started out as Gaozong’s concubine but soon rose to become the real power behind the throne. After Gaozong’s death, she became Empress Dowager and in 690 CE, she demoted her son Ruizong and became emperor in her own right.

Upon seizing control, Wu Zetian changed the dynasty’s name to Zhou. Her reign was a time of great prosperity. She used her talents as an administrator, diplomat and military strategist to expand the Tang borders in Central Asia and bring the Korean Peninsula under Tang control.

Wu Zetian, China's only female emperor, was an able administrator.

Wu Zetian also reformed the imperial examination system to make it more meritocratic, instituted popular agricultural and military reforms and increased state support for Taoism, Buddhism and education.

As someone who challenged traditional gender roles, Wu Zetian was and is a controversial figure. She has often been described as cruel and ruthless and has been accused (perhaps falsely) of killing her own baby daughter. Modern historians, however, tend to view her in a more favorable light.

The Tang at its height

In 705 CE, Wu Zetian’s son Zongzhong deposed his mother and seized the throne, restoring the Tang. After a period of political infighting, Wu Zetian’s grandson Emperor Xuanzong ascended the throne in 713 CE.

Xuanzong presided over the Tang’s most prosperous period. He instituted many reforms, abolishing the death penalty and building an army consisting of experienced soldiers instead of forcibly conscripted peasants. He promoted foreign trade, improved the empire’s infrastructure and increased security along the Silk Road.

During Xuanzong’s reign, the production of books increased due to improvements in woodblock printing, which led to increases in literacy. The common people’s standard of living greatly improved and the empire prospered.

The Tang dynasty was one of the most prosperous periods in Chinese history.

Unfortunately, Xuanzong gradually lost interest in governing and began spending too much time with his concubines, especially his favorite, Yang Guifei. Soon, various corrupt officials began to accumulate power.

During this time, the newly meritocratic imperial examination system also began to falter. Regional military governors called jiedushi (节度使 or jiédùshǐ) began amassing power.

Eventually, the jiedushi established near autonomous hereditary rule over their northern domains, breaking the power of the imperial exams to choose the most qualified candidates for official office.

The An Lushan Rebellion

One non-Han jiedushi who gained power in the later years of Xuanzong’s reign was An Lushan. In 755 CE, he launched a rebellion against the Tang which lasted until 763 CE. He captured the Tang capital and founded his own country, Yan.

The An Lushan Rebellion was one of history’s deadliest wars, killing somewhere between 13-36 million people. The rebellion also resulted in economic devastation and a massive loss of territory.

The An Lushan Rebellion was one of the deadliest wars the world has ever known.

Decline and fall

Although the Tang dynasty enjoyed a modest revival under Emperor Xianzong, who challenged the power of the jiedushi, it continued to decline throughout the 9th century. As the government’s central authority collapsed, the country was wracked by natural catastrophes, famines and rebellions.

Eventually, the Tang was overthrown by a jiedushi named Zhu Wen. His reign ushered in the chaotic Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period in which various jiedushi warlords vied for power. This period lasted from 907 to 979 CE, when the last of the competing states were subdued by the nascent Song dynasty (960-1279 CE).

The Tang dynasty rulers instituted a variety of political and social reforms during this uniquely prosperous historical period.

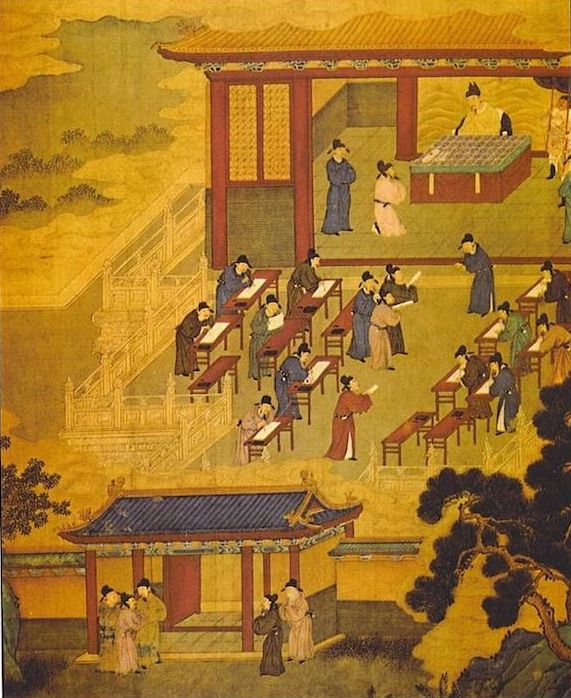

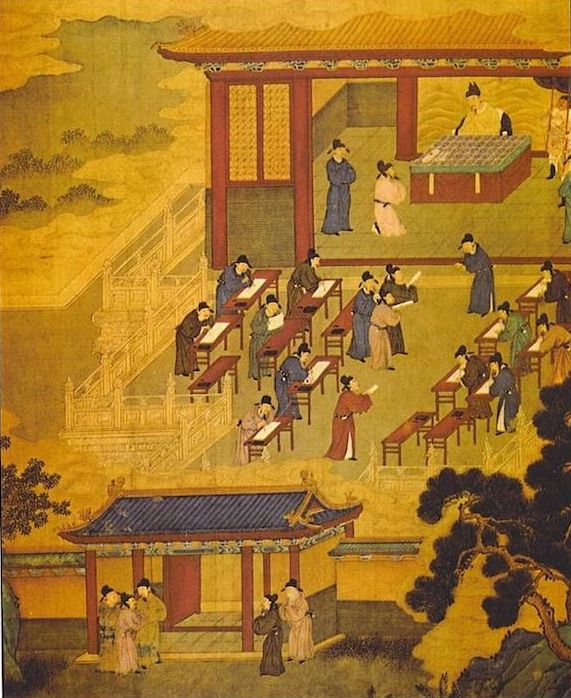

Imperial exams

The concept of using some form of examination to choose the most qualified candidates for jobs within the Chinese bureaucracy existed since at least the Han dynasty (202 BCE-220 CE).

However, a mature system of meritocratic imperial exams (科举考试 or kējǔ kǎoshì) didn’t truly take root until the Tang.

Emperor Wu Zetian made important improvements to the exam system. To maintain control, she needed to reduce the power of her husband’s family and the traditional aristocracy. This goal led her to expand, reform and democratize the imperial exam system.

Wu Zetian also made the exam anonymous and opened it to men from a wide variety of class backgrounds, including commoners. These reforms shifted the balance of power and caused important social changes.

During the Tang dynasty, China's imperial examination system underwent important reforms that helped make it more meritocratic.

After Wu Zetian’s reign, the exam system began to decline as the jiedushi began accumulating hereditary power.

Wu Zetian’s meritocratic exam system returned to prominence during the Song dynasty, however, and continued to be extremely influential until it was abolished in 1905.

Interestingly, the practice of using competitive examinations to choose candidates for government posts in the Western world was modeled after the Chinese imperial exams.

Religion

The Tang dynasty was a time of great religious diversity. Buddhism, which had arrived from India sometime during the Han, rose to prominence during the early Tang. Various different Buddhist schools grew popular with the elite. One of these was Chan, a Buddhist-Taoist hybrid from which Japanese Zen eventually developed.

The monk Xuanzang also made his epic 17-year journey to India and back during this period. From India, Xuanzang brought back an extensive collection of Sanskrit Buddhist texts which he spent years translating. His travels inspired the great Chinese classic novel Journey to the West.

In addition to Buddhism, Tang China was also home to a great deal of other “foreign” religions including Nestorian Christianity, Zoroastrianism, Islam and Manichaeism.

Buddhism became very influential in China during the Tang dynasty.

Status of women

There were many powerful women during the Tang period. Princess Pingyang led a huge army and helped to found the dynasty, Wu Zetian became emperor and many other prominent and politically powerful women also emerged during this time.

Tang women participated in the social and commercial life of the empire. There were many female writers and poets, such as the Song sisters. Well educated women worked as Daoist nuns and high class courtesans. Women were also traders, secretaries, weavers and dancers.

Tang dynasty women enjoyed a life of relative independence.

Tang dynasty standards of feminine beauty were quite different from the standards of beauty popular in China today. Being thin is an essential aspect of beauty in modern China, but during the Tang, overweight women were considered more attractive.

Plump, outspoken, opinionated and assertive Tang women enjoyed dressing up in men’s clothes and playing sports, especially polo.

Although the Tang was undeniably a patriarchal society, it was still incredibly enlightened compared to the subsequent Song dynasty, which saw the rise of foot binding and the cult of widow chastity.

The Silk Road and maritime trade routes

During the Tang Dynasty, the Silk Road (丝绸之路 or Sīchóuzhīlù), which had existed since the Han, was reopened and revitalized. It prospered in part because of Tang era territorial expansion which gave the Tang rulers control over crucial parts of Central Asia.

Over the Silk Road flowed not just silk, but also an enormous number of other products, people and ideas. Much of the famous Tang cultural diversity had its roots in Silk Road trade exchanges.

The Tang economy also benefited from the existence of strong maritime trade routes. Chinese traders were active in far-flung places like the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Peninsula and Africa. China was already manufacturing a huge range of goods for export by this time, and foreign demand for them drew traders from around the world.

Tang-era statues depicting people from foreign lands, like these, demonstrate the influence that increased contact with foreign cultures had on Tang dynasty art.

Art and culture

Robust trade links with other regions of the world helped infuse Tang art with many new ideas. Foreign dances, songs, fashions and musical instruments became popular in China at this time. Elaborate sancai (三彩 or sāncǎi) pottery wares were created. These frequently depicted foreign merchants and their camels as well as the horses used in territorial conquest.

The popularity of Buddhism led to the creation of many elaborate works of Buddhist art while improved printing techniques and an increased emphasis on education led to an impressive outpouring of literature and poetry.

Three of the Tang Dynasty’s most impressive cultural achievements are the Longmen Grottoes, the Mogao Caves and the works of the poet Li Bai.

Sancai pottery was popular during the Tang.

The Longmen Grottoes and the Mogao Caves

The Longmen Grottoes (龙门石窟 or Lóngmén Shíkū) in Luoyang, Henan, and the Mogao Caves (莫高窟 or Mògāokū) in Dunhuang, Gansu, contain some of the finest examples of Chinese Buddhist art in existence.

Although both UNESCO World Heritage sites were begun before the Tang, some of the most important work was carried out during this period.

The Longmen Grottoes are a system of 2,345 artificial caves featuring 100,000 interior and exterior statues. Wu Zetian sponsored some of the site’s most impressive works, including its largest Buddha statue, said to have been modeled after the emperor herself.

The Longmen Grottoes are a treasure trove of Tang dynasty Buddhist art.

The Mogao Caves are carved into a cliff near the once-bustling Silk Road oasis town of Dunhuang. The site is particularly notable because the delicate, colorful murals on the cave walls have been almost perfectly preserved thanks to the desert climate.

These amazingly detailed murals provide great insight into the lives of the Tang dynasty elite, many of whom financed the site’s construction.

Li Bai

The poet Li Bai (李白 or Lǐ Bái) was an adventurous, romantic figure whose poetry is full of fantastic imagery. His work provides a window into the extraordinary times in which he lived and covers a broad range of themes like friendship, drunkenness and travel.

The Tang Dynasty was the golden age of Chinese poetry and Li Bai’s poems are some of the period’s most representative works.

The Tang dynasty gave birth to Li Bai, one of China's greatest poets.

Around 1,000 of Li Bai’s poems survive, and 34 of them are represented in Three Hundred Tang Poems (唐诗三百首 or Tángshīsānbǎishǒu), a poetry anthology which remains required reading for Chinese school children.

A cosmopolitan golden age

The Tang Dynasty emperors ruled over a prosperous, multiethnic and cosmopolitan empire. Viewed from the 21st century, their tolerance for diversity seems surprisingly modern.

The Tang capital Chang’an (present-day Xi’an), with a population of 2 million people, was the world’s largest city. Contemporary port cities like Guangzhou were filled with an impressive mix of people. Arabs, Hindus, Jews, Christians, Bengalis, Khmers, Persians and Malays lived side-by-side, exchanging both goods and ideas.

At its height, the Tang court received tribute from 72 different states, ruling over a vast territory and ushering in a period of Pax Sinica in Asia. Tang culture had a profound influence on neighboring countries like Japan and Korea and contributed to economic growth all across Central Asia.

The Tang dynasty was a time of immense prosperity and cultural diversity.

The Tang legacy

All of this openness and tolerance began to erode in the dynasty’s later years, when the Tang began to experience what Amy Chua, in her fascinating book Day of Empire, describes as a backlash against the very diversity and spirit of tolerance that helped make the empire great.

Whatever the reasons for its collapse, the Tang Dynasty lives on through its art and literature and through the profound influence it had not only on China, but on other countries in both Asia and the West.

Key Tang dynasty vocabulary

| Hànzì | Pīnyīn | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 历史 | lìshǐ | history |

| 历史学家 | lìshǐ xuéjiā | historian |

| 唐朝 | Tángcháo | Tang dynasty |

| 朝代 | cháodài | dynasty |

| 黄帝 | huángdì | emperor |

| 皇后 | huánghòu | empress (wife of the emperor) |

| 科举考试 | kējǔ kǎoshì | imperial civil examination |

| 丝绸之路 | Sīchóuzhīlù | Silk Road |

| 贸易 | màoyì | trade |

| 战争 | zhànzhēng | war |

| 包容 | bāoróng | tolerance |

| 多元化 | duōyuánhuà | diversity |

| 繁荣 | fánróng | prosperous; thriving |

| 三彩 | sāncǎi | three-color glazed pottery |

| 龙门石窟 | Lóngmén Shíkū | Longmen Grottoes |

| 莫高窟 | Mògāokū | Mogao Caves |

| 李白 | Lǐ Bái | Li Bai, a famous Tang poet |

| 唐诗三百首 | Tángshīsānbǎishǒu | Three Hundred Tang Poems, a poetry anthology |

Anne Meredith holds an MA in International Politics and Chinese Studies from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS). As part of the graduation requirements for the program, Anne wrote and defended a 70-page Master's thesis entirely in 汉字 (hànzì; Chinese characters). Anne lives in Shanghai, China and is fluent in Chinese.