Guan Zhong (管仲): The Statesman Who Made Qi a Powerhouse

Learn Chinese in China or on Zoom and gain fluency in Chinese!

Join CLI and learn Chinese with your personal team of Mandarin teachers online or in person at the CLI Center in Guilin, China.

In the long sweep of Chinese history, few advisors loom as large as Guan Zhong (管仲 Guǎn Zhòng)—a Spring and Autumn–period statesman remembered for turning the State of Qi (齐国 Qíguó) into a powerhouse of wealth, organization, and regional influence.

In this guide, we’ll explain who Guan Zhong was, what ideas he’s associated with, why Confucius praised him (controversially), and how the classic text Guanzi (《管子》 Guǎnzi) shaped later Chinese thinking about governance, economics, and statecraft.

Table of Contents

Explore CLI’s Chinese Immersion Program

Who was Guan Zhong?

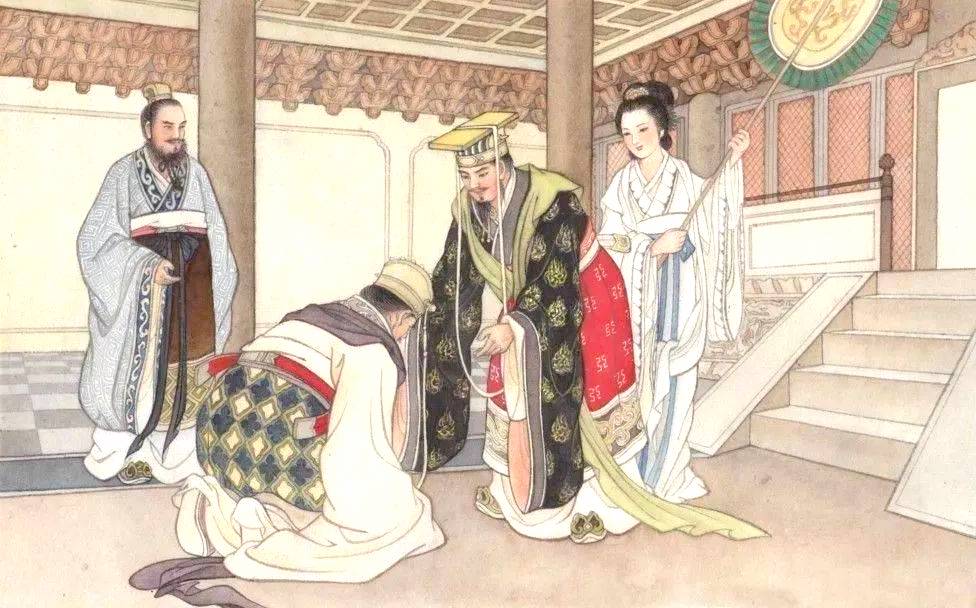

Guan Zhong (管仲) is traditionally remembered as the chief minister of Qi during the Spring and Autumn period (春秋时期 Chūnqiū shíqī). He is most closely associated with Duke Huan of Qi (齐桓公 Qí Huángōng), one of the era’s dominant rulers.

In the broadest sense, Guan Zhong became famous for a simple (but difficult) agenda: make the state rich, organized, and governable. Later tradition credits him with strengthening institutions, improving administrative capacity, and treating economic policy as a core tool of governance—not a side issue.

If you’re new to Chinese historical reading, it helps to orient your “map” of cultural material. Start with our Chinese culture collection, then use the Chinese literature guide to understand how classical texts (like the Analects and Guanzi) fit into the broader tradition.

Guan Zhong (管仲), chief minister to Duke Huan of Qi, is remembered for transforming Qi into a powerful and well-organized state through pragmatic governance and innovative economic policy.

Guan Zhong’s “legend”: why he became a symbol of statecraft

In Chinese historical memory, Guan Zhong represents a particular archetype: the high-capacity minister who builds systems that outlast personalities. When later thinkers argued about how to govern—whether through moral cultivation, strong institutions, clear incentives, or economic management—Guan Zhong was often invoked as an early exemplar of “practical” governance.

1) Governance as systems, not slogans

A recurring theme in later discussions of Guan Zhong is that good government depends on repeatable structures: predictable rules, administrative routines, and coordination mechanisms that make a state coherent.

For modern readers, this matters because it reframes “leadership” as design. A ruler’s vision is limited without implementation capacity—and Guan Zhong’s reputation largely rests on building that capacity.

2) Economics as a tool of political stability

Guan Zhong is also linked (especially through the Guanzi tradition) to the idea that economic conditions—prices, resource flows, production incentives, and household stability—are not “below politics.” They are politics.

This is one reason his name is frequently associated with “statecraft” chapters in the Guanzi, including discussions that treat markets and material resources as levers of order.

Confucius on Guan Zhong: praise that surprised later readers

One of the most cited reasons Guan Zhong remains famous is that Confucius spoke positively about him in the Analects (《论语》 Lúnyǔ)—even though Guan Zhong is not usually framed as a “Confucian moralist.”

A famous line from the Analects

In one passage, Confucius credits Guan Zhong with helping Duke Huan bring order among the feudal lords “without weapons of war,” and in another he adds a striking cultural claim: without Guan Zhong, “we would now be wearing our hair disheveled” and fastening our robes in the “barbarian” style (i.e., left-over-right).

Why does that matter? Because it shows what Confucius valued in this case: political stabilization that preserved Zhou cultural norms. Even for a thinker who prioritized moral cultivation, the prevention of disorder mattered—especially if disorder meant cultural breakdown.

For readers interested in how norms and social order relate, see Chinese society & family, which explores long-running cultural concepts (hierarchy, roles, social obligation) that shape how “order” is understood in different historical contexts.

What is the Guanzi (《管子》), and did Guan Zhong write it?

The text most closely associated with Guan Zhong is the Guanzi (《管子》). But it’s important to be precise: the Guanzi is widely treated in modern scholarship as a heterogeneous compilation rather than a single-author work.

A “library,” not a single voice

The Guanzi contains material that later readers grouped under multiple philosophical tendencies—often including passages that feel “administrative,” “economic,” “ritual,” or “cosmological.” In other words, it reads less like one person’s manifesto and more like a curated toolbox of statecraft ideas assembled over time.

Why the attribution still matters

Even if Guan Zhong did not author the entire text, attaching his name to the collection signals something about how later generations remembered him: as the emblem of practical governance and institutional design. The “Guan Zhong brand” became a way to label a certain kind of approach to ruling.

If you want to read about figures like Guan Zhong in Chinese—even at a basic level—learning a few high-frequency historical and governance terms helps a lot.

| Chinese | Pinyin | Meaning / why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| 管仲 | Guǎn Zhòng | The statesman this article is about |

| 齐国 | Qíguó | The State of Qi; a major power in the Spring and Autumn period |

| 齐桓公 | Qí Huángōng | Duke Huan of Qi; ruler most associated with Guan Zhong |

| 春秋时期 | Chūnqiū shíqī | Spring and Autumn period; early “competitive states” era |

| 论语 | Lúnyǔ | The Analects; contains famous comments about Guan Zhong |

| 管子 | Guǎnzi | Classic text associated with Guan Zhong; a compilation of statecraft ideas |

Why Guan Zhong is still worth reading about

Even if you never plan to read classical Chinese in the original, Guan Zhong remains useful for one big reason: he’s a durable reference point for the idea that good governance is engineered—through institutions, incentives, and administrative clarity.

This is also a helpful lens for language learners. A lot of China-related vocabulary in English discussions—“state capacity,” “reform,” “order,” “institutions,” “administration,” “policy”—maps onto Chinese terms that show up repeatedly across history, politics, and culture.

If you want to build Chinese literacy step-by-step, you can pair culture reading with language fundamentals: What is pinyin?, the interactive pinyin chart, and our Chinese grammar guide.

Guan Zhong (管仲) remains relevant today because he exemplifies how effective governance is built through institutions and incentives—a perspective that also helps Chinese learners connect key political and cultural vocabulary across history.

Learn Chinese with cultural context (online or in Guilin)

Reading about figures like Guan Zhong is a reminder that Chinese isn’t just a language—it’s a gateway into a civilization’s debates about ethics, order, wealth, and human nature.

If you want to accelerate your progress, CLI’s programs are built around high-feedback learning and daily practice:

- Chinese Immersion Program (study in Guilin with one-on-one instruction)

- Learn Chinese Online (one-on-one classes from anywhere)

- The CLI Center (Guilin) + Guilin travel guide (what it feels like to study here)

- Apply now (start dates, planning, and next steps)

Sources

- Chinese Text Project: Analects (Xian Wen / 宪问) — passages discussing Guan Zhong

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “Legalism in Chinese Philosophy” (context on early Chinese statecraft traditions and the Guanzi as a compiled text)

Related guides:

- Chinese literature guide (how to approach classical texts and historical sources)

- Chinese culture (broader cultural context for reading about Chinese history and ideas)

- Chinese society & family (roles, norms, and social order across Chinese history)

- Types of Chinese characters (how the writing system works at a structural level)

- Chinese character etymology (how meanings evolve across time)

- What is pinyin? + pinyin chart (pronunciation foundations)

- Chinese Immersion Program (learn Chinese with intensive one-on-one instruction in Guilin)

The Chinese Language Institute (CLI) is a center for Chinese language and cultural studies based in Guilin, China. Founded in 2009, CLI has hosted over 5,000 students from more than 50 countries and maintains a 4.95 out of 5.00 rating on GoOverseas. CLI's team includes Chinese language educators, program managers, and China specialists holding advanced degrees in Chinese studies, teaching Chinese as a foreign language, education, and related fields. Articles published under The CLI Team draw on the collective expertise of this group, informed by years of experience designing and delivering Chinese language immersion programs in Guilin and across China.