Beginner’s Guide to Chinese Calligraphy

Tania Yeromiyan

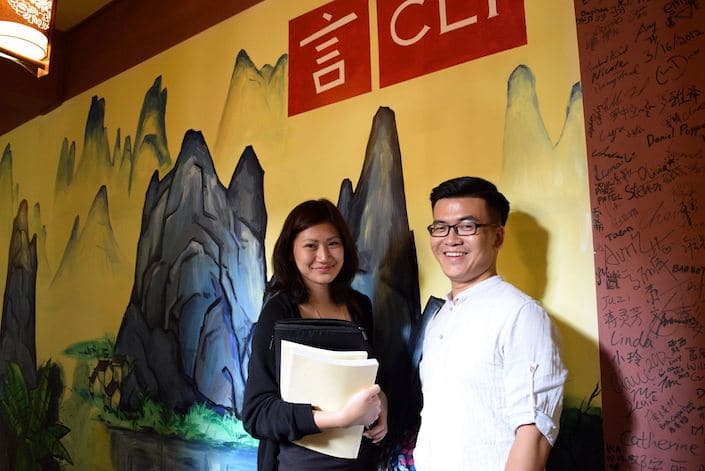

Tania YeromiyanLearn Chinese in China or on Zoom and gain fluency in Chinese!

Join CLI and learn Chinese with your personal team of Mandarin teachers online or in person at the CLI Center in Guilin, China.

Ever wondered about the history of Chinese calligraphy or its different styles? Calligraphy is an integral part of Chinese artistic culture, and calligraphic works are considered beautiful in their own right.

Read on for a better appreciation of this ancient art form through an exploration of calligraphy etiquette, tools, and history.

Table of Contents

What is Chinese calligraphy?

Chinese calligraphy (书法 shūfǎ) is the ancient art of Chinese handwriting. It is an artistic way of writing Chinese characters, which offer an important channel for the appreciation of traditional Chinese culture. (If you’re new to Pinyin, see our Pinyin chart.)

Chinese calligraphy conveys the thoughts and emotions of the calligrapher while revealing the abstract beauty of each character. It has a long history in Chinese culture, spanning thousands of years.

A calligrapher gracefully paints Chinese characters with brush and ink — an art form known as shūfǎ (书法), which expresses both emotion and beauty while preserving thousands of years of Chinese cultural tradition.

The origins of calligraphy

Today, calligraphy is most often practiced as a meditative art form, but it’s important to note that in ancient China, calligraphy was more than just a hobby. It was an essential skill, just like being able to handwrite letters in cursive once was before the advent of computers and email.

Chinese scholars and officials wrote government documents by hand, and when they did so, what we now call calligraphy was simply the technique they used to handwrite characters using writing brushes.

Students in ancient China also used calligraphy to write the infamous imperial exams by hand.

Chinese calligraphy rose to prominence during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). Initially, it was practiced mainly by educated men and some noblewomen, as literacy was rare among ordinary people.

Over time, as its popularity spread among the elite, the ability to render graceful, well-formed characters by hand became a mark of refinement, learning, and social prestige.

Soon, calligraphy was enshrined as one of the Six Arts (六艺 liùyì) that formed the foundation of education in ancient Chinese culture. Alongside calligraphy, these arts included ritual practice, music, archery, chariot driving, and mathematics.

Chinese Language Institute (CLI) students observe a calligrapher at work, learning how the ancient art of Chinese calligraphy began as a vital skill for scholars and evolved into a refined expression of culture and tradition.

The five main scripts of ancient Chinese calligraphy

In Chinese calligraphy, Chinese characters can be written according to five major styles or scripts, namely Seal (篆书 zhuànshū), Official/Clerical (隶书 lìshū), Regular (楷书 kǎishū), Running/Semi-Cursive (行书 hángshū) and Cursive Script (草书 cǎoshū).

Each script comes with its own aesthetic feel, so scripts are chosen based on the type of calligraphy the artist intends to create.

For example, Seal Script is an ancient script that is illegible to many, but it is the oldest style that is still widely practiced today. Cursive Script is loose and has a flowing texture, creating a beautiful and abstract appearance.

Regular Script is arguably the clearest and most legible, which helps explain why this script is frequently used to write Chinese characters in both print and digital media.

As a result of its relative simplicity, Regular Script is generally the first script used to teach calligraphy to beginners, as it provides them with a solid foundation that will leave them well prepared to tackle more advanced, flowing styles later.

Because Chinese characters also appear in other East Asian writing systems, you may also enjoy our comparisons: Chinese vs Japanese and Chinese vs Korean.

Chinese calligraphy features five main scripts—Seal, Clerical, Regular, Running, and Cursive—each with its own distinct beauty, from the formal precision of Regular Script to the expressive flow of Cursive.

Calligraphy etiquette

Chinese calligraphy is not just about getting a character onto the page. The art of calligraphy comes with its own set of rules that continue to be observed and respected by modern calligraphers in China today.

Brush holding

There are some basic rules that one must apply when it comes to holding the calligraphy brush.

In general, the brush should be held firmly in an open palm, and movement of the brush should be guided by turning and twisting the wrist, not the arm. Depending on the type of script one has in mind, the brush may be gripped either at the top or closer to the bottom.

There are several different brush holding techniques, such as:

- 枕腕 (zhěnwàn) – Writers using this technique rest their wrists on a table or on top of their non-writing hand. This technique is typically used by beginners.

- 提腕 (tíwàn) – Writers using this technique lift their wrists slightly while resting their forearms on the table.

- 悬腕 (xuánwàn) – Writers using this technique hold their elbows and wrists suspended above their writing tables with no support. This method is typically used by more experienced calligraphers and those who wish to write using cursive or running scripts.

Chinese calligraphy follows time-honored techniques and rules, including specific ways to hold and move the brush. From resting the wrist to writing with a fully suspended arm, each method reflects the artist’s skill and the graceful discipline behind this ancient art.

Posture

In addition to mastering brush holding techniques, calligraphers must also involve their whole body in the creation of calligraphic art. When seated, the head, neck and shoulders should be relaxed, maintaining an upright and straight torso with both feet on the ground.

If the calligrapher is standing, they generally place their non-brush holding hand on the table for support while tilting forward slightly towards the table.

Chinese calligraphy is a full-body art form, requiring relaxed posture, balanced movement, and precise coordination between mind, body, and brush.

Chinese calligraphy materials: The Four Treasures

The materials used to create Chinese calligraphy are generally referred to as the Four Treasures (文房四宝 wénfángsìbǎo) and include the brush (毛笔 máobǐ), ink (墨 mò), paper (纸 zhǐ) and inkstone (砚 yàn).

Brushes

Traditionally, calligraphy brushes in ancient China were made from a mixture of different animal hairs. The oldest brush discovered so far dates back to the Han dynasty.

Modern brushes are mainly made from goat, rabbit or weasel hair or a combination of these three. Brushes are classed as soft (软毫 ruǎn háo), mixed (兼毫 jiān háo) or hard (硬毫 yìng háo). Different brushes also have different ink capacities, which result in different brushstroke styles.

Brush handles are generally made from Chinese bamboo, though you can also find special high-end brushes which are made from carved bone or even jade.

Ancient Chinese calligraphers wrote on bamboo and wooden slips, the original medium for recording texts and art. Image credit: An 18th-century edition of The Art of War made with bamboo strips. Photo by vlasta2, bluefootedbooby on Flickr / CC BY 2.0

Paper

If you didn’t know already, paper is one of the four great Chinese inventions. Prior to this invention, though, one of the most widely used writing surfaces was actually bamboo. In fact, The Art of War was originally written on bamboo slips!

After the invention of paper, calligraphers began to use a variety of differently processed types of paper to create their works of art. Today, there are many types of calligraphy paper available. Calligraphers can choose paper with different levels of thickness and hardness and these factors impact how much ink is absorbed and how strokes render.

There is also a wide variety of training papers available for calligraphy students. The paper that students use to practice their skills comes printed with square boxes that are used to help guide students in their writing.

Today, calligraphers select from a variety of papers with different textures and absorption qualities, while students practice the artform on specially printed sheets that guide their strokes.

Ink and inkstone

Historically, the ink used for calligraphy was created using soot (lampblack) for black inks and vermilion for red inks.

Modern inks are mainly made from lacquer, oil or pine soot mixed with glue. Some inks also include a mixture of spices used to give them a pleasant aroma to help enhance the overall calligraphy experience. The modern ink-making process generally takes 6 weeks.

Some inks can be bought in liquid form while others are sold as dry ink sticks. Inkstones are used to grind ink sticks into powder, after which slightly salty water is added to the powder on the ink stone in order to create ink of a runny texture that’s ready for use.

Over the years, intricately carved inkstones have become pieces of art in their own right.

The beauty of Chinese calligraphy

Far from being just a page of pretty-looking “squiggles,” each work of Chinese calligraphy is a piece of art that requires incredible brush control and attention to every detail of the overall composition.

Both creating and appreciating Chinese calligraphy require an understanding of the overall philosophy and aesthetic feel behind each piece of artwork.

Experienced calligraphers pay great attention to details like the position of each Chinese character on the page, the different thicknesses of each brushstroke, and how the angles of each stroke can be used to create the illusion of depth and fluid connection to each other.

The practice of calligraphy comes with its own set of rules and etiquette, giving it a sense of formality and reverence and contributing to its important place in Chinese culture.

Chinese calligraphy is beautiful. It is also incredibly difficult, and it takes artists years (and sometimes a lifetime!) to reach a high level of mastery.

If you want to better understand Chinese calligraphy, it is paramount that you learn more about the Chinese characters that make up this ancient art form. We invite you to sign up for a free trial class today and start your Chinese learning journey with CLI.

The Four Treasures of Chinese calligraphy — brush, ink, paper, and inkstone — are essential tools for this ancient art.

Chinese calligraphy vocabulary

| Chinese | Pinyin | English |

|---|---|---|

| 书法 | shūfǎ | calligraphy |

| 六艺 | liùyì | the six arts of rites (the basis of education in ancient Chinese culture which included rites, music, archery, chariotry, mathematics and calligraphy) |

| 篆书 | zhuànshū | seal script |

| 隶书 | lìshū | official script |

| 楷书 | kǎishū | regular script |

| 行书 | xíngshū | running script |

| 草书 | cǎoshū | cursive script |

| 文房四宝 | wénfángsìbǎo | the four treasures of the study (an expression used to refer to the writing brush, ink, paper and inkstone) |

| 墨 | mò | ink |

| 纸 | zhǐ | paper |

| 砚 | yàn | inkstone |

| 毛笔 | máobǐ | writing brush |

| 软毫 | ruǎn háo | soft brush |

| 兼毫 | jiān háo | mixed brush |

| 硬毫 | yìng háo | hard brush |

| 艺术 | yìshù | art |

| 中国传统文化 | Zhōngguó chuántǒng wénhuà | traditional Chinese culture |

| 练习 | liànxí | to practice |

- Chinese stroke order (the foundation of handwriting and calligraphy)

- The 100 most common Chinese characters

- Types of Chinese characters

- Chinese Pinyin chart (with printable PDF)

Tania holds a BA in Arabic and Chinese from the University of Leeds, which led her to spend two years studying in Taiwan and Egypt as part of her degree. Her interests include Chinese traditional theater, international education, and programming. Tania travels to China annually and is fluent in Chinese.